I come from lake folk.

My grandparents ran a ma-and-pa resort in northern Minnesota for 30 years. They'd work constantly during the summer months, pulling fishing boats from storms, answering the steady beckon of doorbell rings, literally putting fires out when lightning struck the red pines. My grandma did it by herself the years money was tight and my grandpa had to pick up a second or third job to make ends meet. The winter brought -40F temps, the occasional snowmobiler, and the promise of odd jobs like School Bus Driver to get through the off season. The work shows in the veins of my grandmother's tanned hands, the kind of veins I'll be proud to have earned one day.

My grandparents taught me grit. I learned what it meant to work hard and to make do with what you have and that friends are everything. When I moved west, I spent two years pushing paper before reverting to my roots. Water rights, food systems, and the future of human and land health became the focus of my livelihood. I don't punch a clock, that's not the kind of work I was after. I work outside and I work with my hands and toes and shoulders, just like my grandparents did for all those years.

I've learned that the natural world spells its story out and that if you learn how to read it you can fix problems before they're irreversible. The gore mark on my stomach reminds me that animals are living beings with intentions of their own and the perpetual dirt under my fingernails reminds me of the energy that goes into producing a single bite of food.

Becoming a rancher has allowed me to immerse myself in the global food crisis and become part of the fight for water in the American west. I see my job as two-fold; firstly, to maintain animal, vegetable, and orchard health so the families of the Roaring Fork Valley can have access to raw milk and locally grown biodynamic food. In addition: to tell the stories of the land, the people who tend to it, and what we can do to ensure the agrarian culture of this valley and those coloring the world's backroads is preserved.

In their backyard

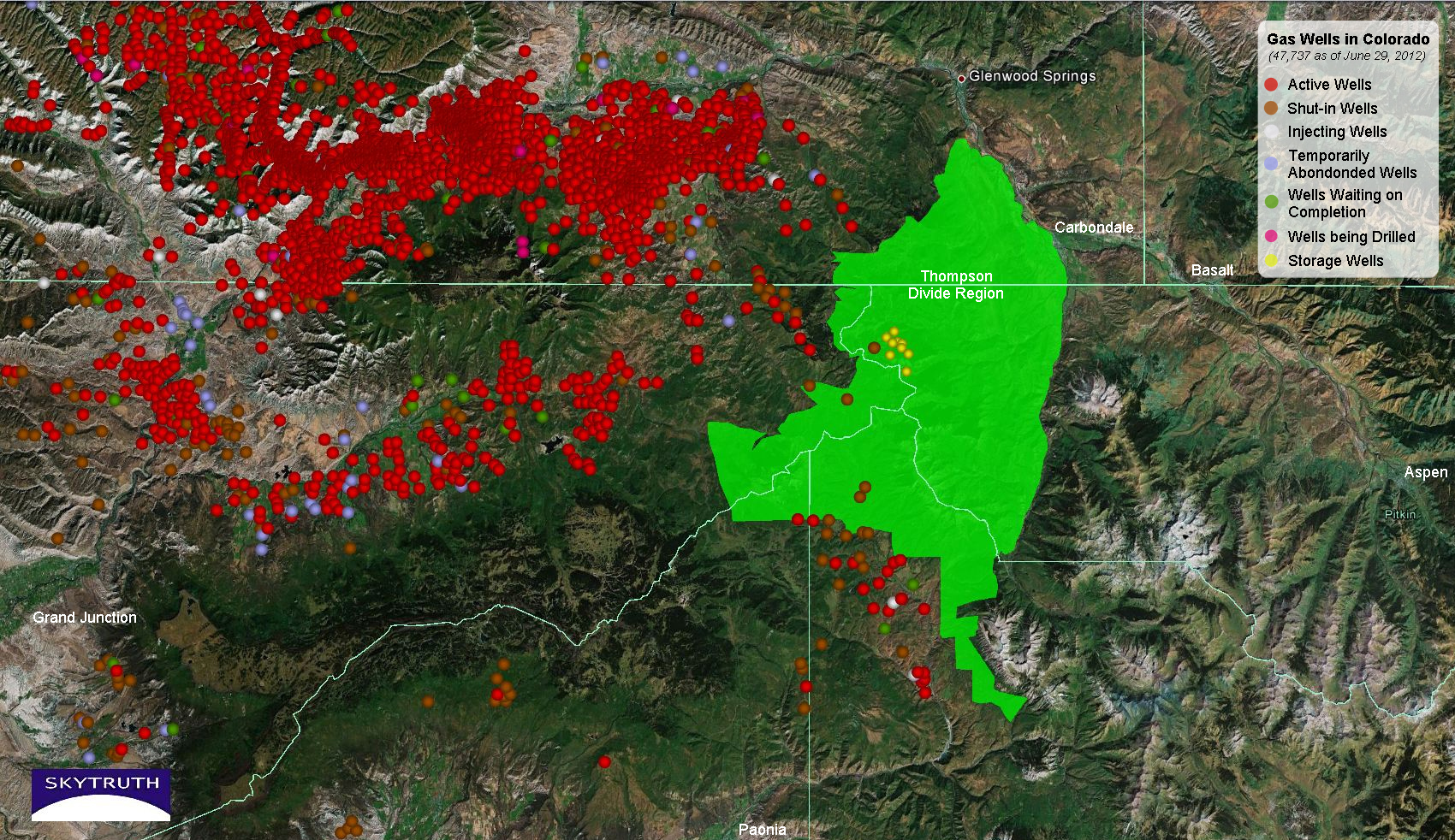

Before South Dakota or Pennsylvania, there was the Piceance Basin: fracking ground zero. With over 25,000 active oil wells, it was here that fracking techniques and equipment were tested before the extraction method boomed seven years ago. The Thompson Divide sits just southeast of ground zero, sprawling 220,000 acres of Colorado's backcountry. It's one of the densest concentrations of inventoried roadless areas in the great American West. It's bounty includes the country's most heavily-recreated National Forest. Existing land uses in the Thompson Divide generate 300 jobs and funnel $30 million into the economy each year. Historically the land of the Ute Indian Tribe, and then a settlement of Polish potato farmers, the Thompson Divide is now home to several small farming and ski towns including the infamous Aspen, Colorado.

While ninety-nine percent of land in the Divide is used for hunting, ranching and recreational purposes, natural resource giants SG Interests, VII (SG) and Ursa Resource Group hold leases here, too. The companies claim that fracking a portion of the wilderness area will bring revenue to the proportionally wealthy area. In retort, residence of Carbondale, Basalt and Aspen argue that the leases sold in the Thompson Divide are on speculative territory, meaning we're not even sure we'll find oil there. The plots were sold for around $2.00/acre because natural gas isn't a guarantee—put that up against plots going for $10,000/acre in the Piceance Basin, and proponents of the land's current uses, recreation and ranching, argue those uses are actually better for the economy. As SGI sees it, the Thompson Divide as a perfectly-positioned swath along its Bull Mountain Pipeline, the main highway for oil coming out of the Pieceance Basin. Layman's SGI stands to make a lot of money if it can link it's existing pipeline to one that cuts through the Thompson Divide Region via the plots it may or may not have legally purchased.

Just above Grand Junction, the Piceance Basin lies under a mass of red dots, active wells.

Plans involving a 30,000 acre lease swap would move fracking from the Thompson Divide's Roaring Fork watershed to the North Fork. The swap would retire only the SG and Ursa leases that do not have active drilling, excluding the Wolf Creek Storage Unit which is considered an active well and whose deep rights are owned by SG. The exchange has been portrayed as a rich vs. poor issue, but it's not that simple.

The North Fork watershed is no stranger to the boom and bust of energy industries. Unincorporated communities throughout Gunnison and Delta Counties--southwest of the Thompson Divide—shrink and expand with industry, and that's how it's been for over a century.

The proposed exchange is shaded dark green, the purple area is the land in which SG has the deep drilling rights and that BLM cannot cancel leases. The Wolf Creek Storage Unit (purple) stores natural gas in a sandstone basin below the water table during the summer. The gas is released when people heat their homes with natural gas in the winter and more is needed. The map also shows SG's $60 million Bull Mountain Pipeline.

It'd be easy to miss Somerset if you blinked on CO-133. There's a post office, a cafe, a coal mine, and on the years the Oxbow mine shuts down, rows of abandoned turn-of-the-century homes. Mineral extraction has been the livelihood of this area for generations, and when a town relies almost entirely on a mine that eliminates as many as 300 jobs when it idles, people look for more stable options. Historically, most of the oil wells in the North Fork Valley are a result of private land being leased to companies like SG. As a result, SG is actively drilling 156 new wells in the Bull Mountain area near Somerset. SG is using traditional overpressured wells to extract as much oil as possible, as quickly as possible, funneling it into the Bull Mountain Pipeline. The leasing of private land to natural resource companies in the North Fork River Valley, Colorado's fruit basket, is already putting pressure on the farming communities that have an equally rooted culture in Gunnison, Mesa, and Delta counties. Additional drilling would add to the inherent issues of fracking, especially contaminated irrigation water.

This is an issue of economic prosperity, but not in the simple way people like to claim when they're looking for someone, or some organization, to take the blame. "We don't have the money to support organizations that will fight for us, up here, we're doing it at the grassroots level," said one Paonia farmer. The Thompson Divide's location makes it easier (and even possible, for that matter) to hire people like Zane Kessler of the Thompson Divide Coalition to fight for new legislation. He's also confident the lease swap won't go through. It requires Congressional action and the BLM is already investigating whether or not the Bush-era leases should have been issued in the first place (i.e. many speculate the leases were issued illegally because the environmental study protocol was not carried out).

"This isn't a situation that will be cured with letters," says Kessler. "We're up against Houston-based billionaires who are very good at what they do," says Kessler.

The Thompson Divide Coalition has been fighting the two Houston-based natural resource companies for years. At one point, they offered the companies twice as much as they had originally paid for the leases—around $2.5 million—to abandon them. Since stepping in, the Bureau of Land Management is exploring the possibility of retroactively canceling the leases, meaning refunding SG and Ursa's original leases for the amount they paid at the time of purchase and protecting the land's mineral table from any future leases. Proponents of the swap argue that it isn't about the economic prosperity of a region as much as it is protecting public land in the midst of private land being offered up to natural gas companies.

In the end, a straight lease-for-lease swap like this has never been done. It requires intervention by Congress, a lengthy process at best. It appears SG in particular is using the Thompson Divide leases as a pawn, holding onto the land to use in an exchange for something more favorable. If the Bureau of Land Management can prove these leases faulty before the case hits D.C., the lease refund can be carried out without the need to exchange the other--more frackable--land, foiling SG's strategy. Ultimately, this is the goal of people fighting to protect the Thompson Divide, a win-win that would eliminate either watersheds to bear the burden.

Thinking in Pictures

If you want respect, you have to dress the part.

It's the unspoken law of the land in ranch country and Temple Grandin is no stranger to this. Monogrammed bolo tie in place, she's pushed past stubborn tradition to reform the American cattle industry. She became one of them in order to change their normal.

Grandin is not with PETA and she's not a vegetarian. She sees what the rest of us go blindly through our day without noticing. "The rest of us" being the non-Autistic population.

"If it weren't for Autism, nothing would get done," Temple jokes.

Grandin was the first Autistic person to explain the disease to the non-Autistic population. She sees in pictures, and because of this, the way animals think is so utterly obvious to her.

"Animals don't think in words. They don't know something is called a lake, but they can picture where they are walking to in their mind," she explained at a talk in Carbondale, CO.

When hanging up posters to advertise the event, I wasn't sure what the turnout would be.

"Oh yeah, that's that lady who lays down with the cows," one fellow rancher spat out when I sealed the tape on a poster outside the local watering hole.

Grandin gave two talks after visiting Sustainable Settings Ranch to give us advice on our new barn design. Both talks sold out. Her talk on ranching filled with the curves of cowboy hats, old time ranchers of a valley known for the lifestyle since the Thompsons settled here 150 years ago. "What's good for the cow is good for the wallet," Grandin proclaimed, resonating with the rancher's need to make a living. She had their respect and deserved to.

Temple Grandin didn't make a name for herself working with dairy cows. It was the slaughter houses and stock yards that caught her focus. None the less, she offered her advice as Zopher, our herdsman, milked ten head the day she visited the ranch.

She confirmed that the cows were chewing their cud during milking, a sign that they were calm; but the concrete floors of the raw dairy needed grooves. Humans don't like walking on slippery surfaces and that goes for cattle, too. She answered our questions diplomatically, but in the key of, "how do you not see this?" To her, the way animals think is obvious. Grandin was given a gift that allows her to leave a lasting mark on the beef industry, a constant taboo of the food system. It's heroes like her the rest of us bow down to, for they are at the forefront of solving the global food crisis.

Chef changing Colorado’s perception of ‘weed’ and it’s not what you think

Chef Will Nolan works weed into his Louisiana gumbo. Or weeds, to be correct. Eating weeds isn’t a new thing and some may say it’s past its heyday (circa 2009), when New Yorkers were encouraged to eat stuff they found next to dog feces and junkies in Central Park. The partnership between chef Will Nolan and rancher Brook LeVan goes beyond formerly trendy and potentially harmful wild foraging: Nolan is supporting local farmers by buying the volunteer plants (weeds) that grow in their gardens. And for more dollars-per-pound than spinach.

Farmers who can work selling weeds into their business plan lower seed costs and significantly cut water use since the plants thrive in unfabricated environments where they’re watered only by natural precipitation. They reduce our reliance on plastic greenhouses and make herbicides (the chemicals that kill weeds while stunting the growth of crops) obsolete.

“A lot of the vegetables we grow here are European or Asian, they’re not really local, they’re just growing here,” says Nolan’s weeds source, LeVan.

As a farmer, he’s working to change ‘eating local’ from eating crops that are pushed to grow in environments they don’t thrive in, to eating plants that will grow whether or not they’re planted—plants whose nutritional content rivals buzzwordy greens like kale. Lambsquarter, for example, can be found in almost every state in the continental U.S. and has over four grams of protein per 100 gram serving. It’s also on Colorado’s weeds list.

“So much of it is just perception. If you never told anyone Lambsquarter was a weed, they’d think it was beautiful,” says Nolan. Making weeds bougie is step one in changing the cultural perception of the plants. Getting people to replace non-native vegetables with wild natives on the daily, that’s where the real difference is made.

Brook LeVan holding a ball of compost teaming with BD prep. It will be used to inoculate the entire compost pile with the microbes that create heathy, living soil.

Biodynamic Farming: What is it and what does it mean for Colorado?

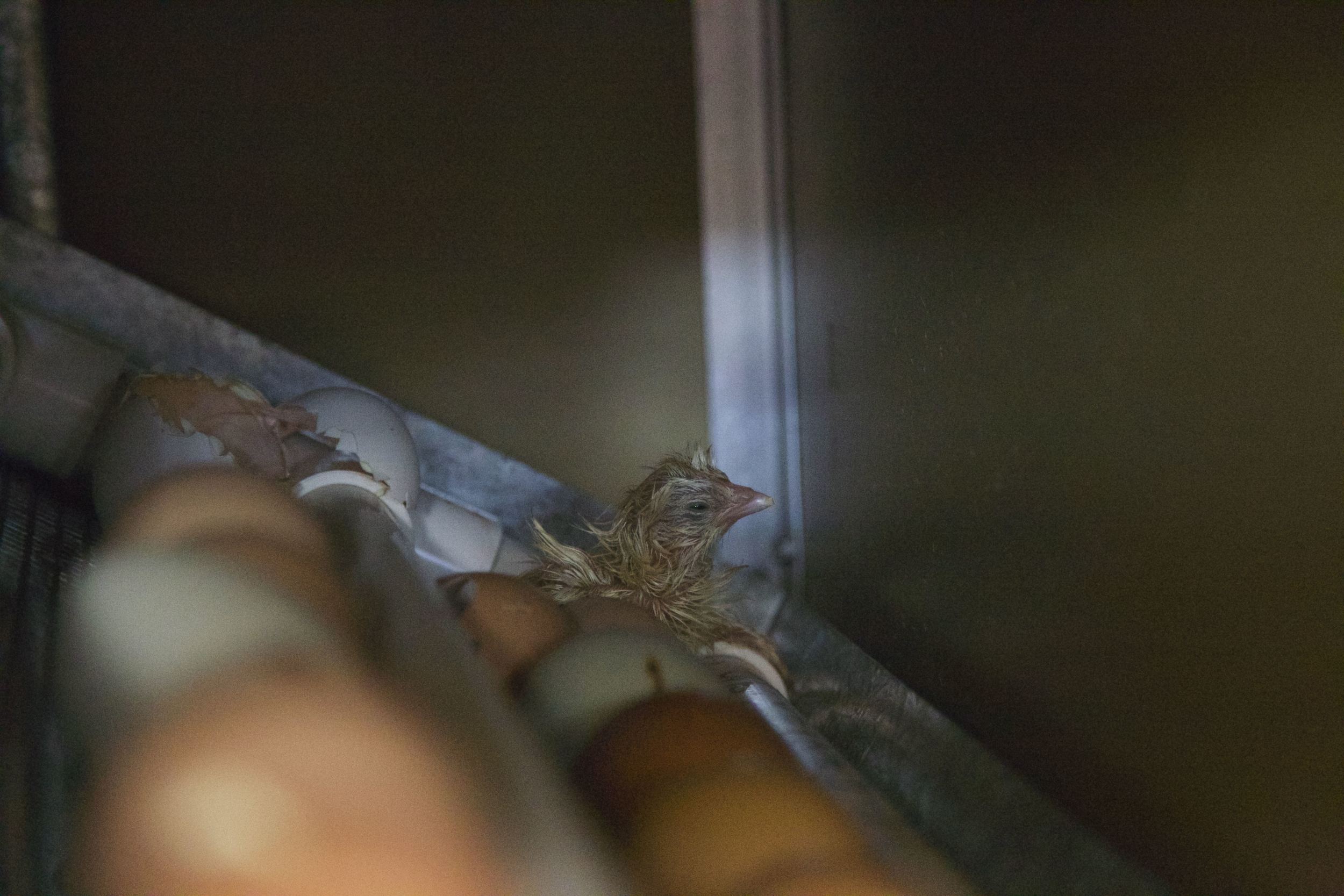

The image of Colorado’s most recently certified biodynamic ranch differs little from organic farms found throughout the state: an adobe coop shelters heritage birds, a hoop house extends the alpine desert’s short growing season, mounds of compost sit in the shadow of a 13,000 foot peak.

If you look closer, you may notice the wheelbarrow of hollow cow horns resting between two stationary pickups, they spent the winter in the ground packed with manure. Or the blue glass decanters and lumps of quartz lining the shelves of an unassuming pine structure on the north side of the property. These are the tools of Brook LeVan who, like the land he and his wife Rose cultivate, appears to fit the quintessential description of “out west,” his image altered only by the color of plaid visible beneath his leather vest. Though as they come, the LeVans founded Sustainable Settings in Carbondale, CO. The learning center and working ranch is one of four certified biodynamic farms in the state and a keystone initiative in Colorado’s biodynamic movement.

Developed in the 1920s, biodynamic food is steadily making its way into the mainstream. Though the wine industry dominates biodynamic agriculture worldwide, grocery giants like Whole Foods have declared their support of biodynamic food. What could be labeled as the next big thing in sustainable food production, biodynamics is often veiled in mystery and snubbed due to its price tag. In an era where efficiency is favored over effectiveness, short term profit over longterm vitality, biodynamics seeks to use agriculture as means to strengthen communities as a whole.

BD 101

"Witchcraft," Brook jokingly told me during my first ranch tour. Jest aside, Biodynamics (Biological Dynamic process) is a holistic approach to farming that views the entire farm as a single organism. Think of a Biodynamic farm as a single living unit composed of many organs—like the human body. Just as illness in one part of the human body will affect the whole, Biodynamics teaches that what occurs in any single part of the farm will affect the entire system. Biodynamic farmers recognize that soils, plants and animals do not exist in isolation. For example, producing quality feed for animals leads to quality manure and compost, which produces quality soil that fosters quality plants. A staple principle of Biodynamic farming is consistently using the byproducts of one area to strengthen the health of another. By creating a diversified farm ecosystem, Biodynamics encourages a closed-loop operation that discourages off-farm inputs and instead generates fertility from within the operation. For example, implementing specific plants that sequester nitrogen from Earth’s atmosphere and pull it into the soil could replace the need for nitrogen supplements produced off-farm. Companion planting is used to create a balance of micro-nutrients like nitrogen, phosphate and potassium in soil, and naturally pest-repellant plants like Tropaeolum (aka nasturtium) reduce the need for pesticides produced off-farm.

Soil fertility is the cornerstone Biodynamic farming. Without the use of manufactured chemicals, practitioners foster healthy soils, plants and animals through more traditional methods that require greater specificity within inputs. Biodynamic compost is built deliberately using preparations. In scientific terms, Biodynamics seeks to increase the number of microbes and fungi that create well-structured soils with higher water-holding capacities, and that require less tilling, fertilizer, and maintenance (yes, kind of like permaculture).

Here's where Biodynamics really differs from other forms of sustainable agriculture: its spiritual aspects. Though compost is rooted in microbiology, BD farming follows strict rules that recognize celestial alignment having significant influence over plant health, rules that are largely rooted in Christianity. Nine in total, each preparation is a strategic mixture of fermented plants, manure, minerals and even parts of harvested animals. Preparations are mixed with compost or sprayed directly onto the land. All but one are buried to ferment underground for a specific period of time. Each preparation is meant to affect soils specifically, for example, introducing minerals deficient in current soil.

Facing Stigma

It's easy for modern farmers, and the general public for that matter, to discount these labor-intensive, spiritual and unconventional methods of food production. But is BD really "unconventional"? Once an almost unanimous practice for agrarian societies, the custom of aligning crop management with the night sky has become archaic among modern farming methods. Everyone from

In contrast, Biodynamic farmers plant and harvest crops according to various biodynamic calendars. Commencing on the first of January, the calendars are unique to the lunar and planetary cycles of each year. Just as the tides are directed by the waxing and waning of our Moon, Biodynamics observes that all celestial bodies have an affect on the growth and behavior of plants. Crops are classified as one of four archetypes: fruit, leaf, root, or flower based on the desired area of emphasis (i.e. carrots are a “root” crop, tomatoes are “fruit” crops). The ideal days to plant and harvest each crop is indicated in each year’s calendar by which constellation the Moon is passing through. According to Demeter, the certifying agent of biodynamics, the calendar is “respected as far as practically possible” given that it is not always possible or appropriate to adhere at all times.

The principles of Biodynamic farming include creating whole systems communities that extend beyond the farms themselves. It was biodynamic farmers that pioneered the widely adopted concept of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA). Initiatives address a triple bottom line approach, that is creating ecological, social, and economic sustainability.

Rudolf Steiner

When Western agriculture was seized by industry in the 1920s the values of industrialization put farmers in position to become stations of commerce, pressured to produce the highest output for the lowest cost. Nitrogen was discovered as a stimulant for plant growth, giving way to the development of synthetic fertilizers.

Famously the mind behind Waldorf education, Rudolf Steiner spent his life developing anthroposophy, sometimes referred to as spiritual science and a pillar of Biodynamics. Steiner was among the first to speak openly of the dangers of chemical fertilizers and by 1922 concerned farmers were seeking him out for advice. They were noticing the degeneration of seeds and plants; their crops were weak.

Steiner delivered The Agriculture Course in Germany, 1924. The pivotal series of lectures introduced the sustainable farming practices he called Biodynamics. The father of anthroposophy had spent years developing nine core Biodynamic preparations that focus on restoring the soil modern methods had void of life, of the microbes and fungi that produce crops of the highest integrity. Steiner’s preparations introduced nitrogen, phosphorous, and calcium as stable parts of cultivated soils. Rather than the reductionist approach of spreading soluble NPK, Steiner built soil holistically; like eating the right food to give the human body adequate nutrients versus taking a vitamin. Working with fellow followers of anthroposophy, he brought his teachings from Europe to the United States in the 1930s, founding the Biodynamic Association in 1938.

Demeter USA

A representative of Demeter International, Demeter Association, Inc. enables people heal the planet through agriculture. The rigorous standards allow worthy producers to market their food under the “Biodynamic®”, “Demeter®”, and Demeter Certified Biodynamic® labels. Farm evaluations include such specifics as whether or not cattle drink from a natural stream. Specific standards for wine making and production ensure accountability from start to finished product.

Demeter doesn’t snub organic, either, recognizing it as a foundation from which biodynamics builds upon. Demeter’s Stellar Certification Services was one of the first organic certifiers to earn NOP accreditation after the USDA created the body to regulate the use of “organic” in the consumer market. Demeter certified Biodynamic® producers who don’t want to lose their organic certification can legally label their food as organic through the Stellar certification. When the story of the indentured farmer is all too common, Demeter’s aim is not to add to the massive debt tied to agriculture. Stellar streamlines the daunting application process for farmers seeking both organic and Biodynamic® certifications: one application fee, one inspection, one royalty fee.

Legal obligations aside, Demeter is more than a policing body. The nonprofit organization serves as a resource for biodynamic and organic farmers. What makes the organization stand out is the way it works to connect farmers and encourages the community to collaborate. Many members of the certifying body run Biodynamic® farms of their own and the process resembles a mentorship more than a government of textbook standards.

As Lance Hanson of Colorado’s Jack Rabbit Hill puts it:

“The Biodynamic Demeter program is not just a policing effort, it’s an educational opportunity. To us, that’s the most important aspect to our relationship with Demeter USA, the value we get from their farming expertise. The Demeter certifying body includes farmers themselves. They have working Demeter farms so they talk to you from the perspective of people who are doing it. It makes their guidance that much more relevant and potentially much more effective.

DemeterLOCAL

With just seven certifiers, the DemeterLOCAL initiative promotes growth in regional Biodynamic food sheds. It offers an alternative Biodynamic® certification for farmers who produce and sell product with 200 miles of their farm. Still new, the unique certification process empowers farmers and builds solid communities through peer-to-peer certification. The peer-to-peer model addresses the critical issue of high overhead faced by small farmers. The certification fee is less than one-third of the national Demeter certification, helping small farmers compete with big agriculture.

Farms are certified by peers using the seven core principles outlined in the U.S. Demeter Biodynamic Farm Standard. Under the current model, farms are certified by peer Biodynamic experts that may fall under three categories.

Farmer to Farmer model

A group of farmers in a local food shed work together to ensure the Demeter Biodynamic Farm Standard is being met throughout the community. They work together to exchange knowledge and ensure integrity. Only a farmer that is accredited through Demeter is able to certify fellow farms using the Farmer to Farmer model.

Education Institution model

Students are the certifiers in the Education Institution model. Farms working as a living classroom and teaching Biodynamic agriculture are evaluated by Demeter accredited students. Using the Demeter Biodynamic Farm Standard as a base curriculum, visiting students confirm the standard is being met.

CSA model

If a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) member is accredited through Demeter, that member or group of members can verify a farm complies with the seven core principles of the U.S. Demeter Biodynamic Farm Standard.

What Colorado is Doing

Tamping grapes for a 2016 Pino Noir.

Jack Rabbit Hill | Hotchkiss, CO

In 2001, Lance and Anna Hanson were on a mission to turn 18 acres of western Colorado countryside into Pino Noir, Resiling and Chardonnay. They were quite successful. Three years later the winegrowers began exploring different ways to step up their organic farming practices.

“We wanted to produce the best quality grapes and wine that we could—denser root systems, more microbes and insects because we believed that ecosystem would foster stronger healthier vines,” says Lance.

When he discovered Rudolf Steiner’s 1924 lectures, Lance admits it took some effort to wrap his head around biodynamics. Jack Rabbit Hill started working closely with Demeter—biodynamics seemed to fit the bill.

After months of research, they wanted to see first hand what people were doing with it. Tours of biodynamic vineyards in California’s Sonoma and Napa counties. “We came back totally convinced that it was for real, it was something that we could and should do as organic farmers and we were in a position to reap real benefits from it,” says Lance.

So they did just that. Jack Rabbit Hill is Colorado’s only Demeter Certified commercial grape grower. Its vineyard spans 18 acres with hops covering another eleven. The Hansons have noticed a difference in the strength of their vines

Biodynamic apples from California produce Jack Rabbit Hill’s biodynamic hard cider—one of the only on the market—but that’s temporary.

“There are lots of backyard movements and that’s great, I encourage all that, but we need to get more commercial orchards on board,” says Hansen. Putting his money where his mouth is, Jack Rabbit Hill provides financial incentives for Colorado fruit growers to produce biodynamic crops.

Jack Rabbit Hill believes in paying premium prices to encourage people to practice the absolute best farming methods. The gain share pricing model was awarded a grant by the state of Colorado.

“Our agenda is to go back to Colorado growers,” says Hansen, “We don’t want to see it become an exclusive club, we want everyone to do it. It’s the secret to really good farming and we want to educate people on it as much as possible.”

Above: Cross combing in an alpine beehive | Healthy BD Larks Tongue kale | Pasture pigs called Kune Kunes bask in the sun | Harrowing potatoes by hand in Sustainable Settings' creek garden | BD Aprentice Stone Hunter sprays preparation 501 on a compost pile | Volunteer Alejandra Rico sorts turnips for Susty's biodynamic CSA.

Sustainable Settings | Carbondale, CO

If there was a catalyst for the boom of Biodynamics in Colorado, Sustainable Settings could claim that title. The working farm and whole systems learning center is the first DemeterLOCAL certifier and certified farm in Colorado. The ranch produces a Biodynamic CSA, as well as certified raw dairy and meat. Most importantly, it is a hub for farm education. A regular stream of school field trips, ranch visitors, volunteers, workshop attendees and industry experts incubates an environment of collaboration and education. The ranch’s internship program draws students from the North American Biodynamic Apprenticeship Program (NABDAP), a two year farmer training program through the Biodynamic Association and an international community of WWOOFers leave with new knowledge of Biodynamic farming techniques.

“Having Sustainable Settings certified will have a significant impact on Biodynamic agriculture in Colorado,” predicts Elizabeth Candelario of Demeter USA. “We will see a ripple effect in that area because they are a stake in the ground.”

Once a professor, Brook LeVan understands that numbers talk. The working ranch puts Biodynamic side-by-side with organic produce and documents differences throughout the growing season. Annual soil samples are sent to the National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) for testing that compares the quantifiable health of Biodynamic and non-Biodynamic soils.

“Agriculture is possibly the greatest, longest experiment in mankind’s history,” says LeVan, who works closely with Lloyd Nelson of Rainmakers Biodynamic Services to hone preparations and techniques.

If you’re looking to delve into Biodynamics, Sustainable Settings is the place to do so. Information on farm visits, internship programs and a calendar of 2016 workshops and events can be found at sustainablesettings.org.

Brook LeVan works closely with Lloyd Nelson of Rainmakers Biodynamic Services. Together they concoct preparations to be sprayed on compost piles and directly onto crops.

Rainmakers Biodynamic Services | North & Roaring Fork Valleys

Lloyd Nelson is a jack of all trades prep maker based in Paonia, CO. “It’s rare you go to a place that has as many Biodynamic activities as Colorado’s North Fork Valley,” says Nelson, who relocated to Colorado from Hawaii after teaching at a Biodynamic conference in Hotchkiss.

Under the name Rainmakers Biodynamic Services he builds preparations for small scale landscapes and gardens, tree rejuvenation and large scale vineyards and orchards. The potency of his preparations have ranked among the best in the nation.

One would be hard pressed to find a Biodynamic initiative on the Western Slope that hasn’t been shaped by Nelson. As a consultant and an educator, his workshops foster more than the obvious outcome of spreading knowledge of Biodynamic techniques. Nelson’s workshops strengthen the global community by facilitating a platform for collaboration. Contact Lloyd of Rainmakers Biodynamic Services at lloydrnelson@gmail.com.

The Future is Bright

Comparatively, Biodynamic farming is but a boutique set of methods scarcely practiced outside the wine industry. Germany leads the way with 1,476 Demeter Certified Biodynamic® farms, the United States trailing with 107, the Columbine State accounting for just four.

“Biodynamics is a recent trend that isn’t yet impacting on a large scale because the percentage of overall farms that are biodynamic is still low,” notes Calendario, though it likely is just the beginning.

National initiatives such as DemeterLOCAL, the hoops that too often deter farmers from becoming certified under any standard are being removed. Educational opportunities are easy to seek out and the unanimous goal is to get more people practicing Biodynamics. Currently there are five Biodynamic farms training apprentices from the Biodynamic Association’s NABDAP program. It is clear that the Biodynamic community is not one of competition, rather a social movement that uses agriculture to heal economies, social structure and land. It is through community that Colorado is doing its part to support accountable farmers who work to shape our communities for the better.

Books

Agriculture Course: The Birth of the Biodynamic Method by Rudolf Steiner

Soil Fertility, Renewal and Preservation by Ehrenfried Pfeiffer

Sacred Agriculture: The Alchemy of Biodynamics by Dennis Klocek

Grasp the Nettle: Making Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Work by Gillian Cole and Peter Proctor

Gardening for Life by Maria Thune

Biodynamic Agriculture by Willy Schilthuis

Online Resources

Biodynamic Association | biodynamics.com

Demeter USA | demeter-usa.org

The Nature Institute | natureinstitute.org/soil/index.htm

Visit a Farm

Aspen Moon Farm

8020 Hygiene Road

Longmont, CO 80503

(303) 808-9583

Jack Rabbit Hill

26567 North Road

Hotchkiss, CO 81419

(970) 835-3677

Lamborn Mountain Farmstead

42229 Lamborn Mesa Road

Paonia, CO 81428

(970) 527-5105

Sustainable Settings

6107 Highway 133

Carbondale, CO 81623

(970) 963-6107

"The times it doesn't work is rehearsal for when it does."

José Miranda’s Toyota is defined by the skilled repairs of someone who knows how to scrape by—happily—with what he has. The manual transmission tacks like the heart of healthy man in his sixties. In the driver’s seat, an inky beard frames an iconic smile and skirts a well-worn hat that’s earned every stain. I latch the chain of a gate that closes one of Tybar Ranch’s pastures and pull myself into the pickup. The cattle here are bred to resist brisket, a disease common in alpine cattle. José knows them all by name and introduces me. At this point I haven’t been a rancher long enough to wear the label, but I do know all the places cows like to be scratched.

After a long day, commencing a string of long weeks making up months, José welcomed me into his home. He generously shared his Pad Thai and even more generously, the tales of a life that lead him to Tybar Ranch, 800 acres accented by Angus beef and the Elk Mountain Range. A week later José’s wife, Kami, welcomed me with the same hospitality. She was tired but hid it well, never glancing sideways at a clock or appearing anything but present. Both shared stories that exemplified the raw grit it takes not only to be a farmer, but to cope with the shower of bullets life can fire at any given moment.

Back home in Venezuela, José owned 3,000 acres. Here, he manages someone else's ranch. He came of age on a family farm so the trying lifestyle was never rose-colored in his eyes. As a teenager, José saw the environmental issues associated with the global food shed and sought solutions, making plans to pursue a career in ranching. The people of Venezuela were in a state of constant strike when José graduated from high school. An unstable government stunted his university education. It took him two years to complete the work of one semester. Instability and frustration carved his new path. He fled the situation in Venezuela that made his education impossible and flew north to work as a ranch hand in Montana. It was here that he eventually proved his dedication to the man who would foot the bill for his degree from Montana State University. I’d like to hug that man myself for the clear impact he made on the man in front of me—a new friend’s—life. José cannot talk about him without doing so through sobs. He let fat tears slide into his beard, knowing the man deserved them.

Enter, Kami. The couple met in West Virginia when she was in her early 20s. Both climbing instructors at a summer camp, their world was warm and easy to decipher. José had just finished his degree and was making plans to return home to his family’s farm, hoping his life-long summer fling would follow. The summer came to a close just before the Twin Towers fell, the catalyst that finally pushed Kami towards Venezuela with uncertainty. She had always wanted to live simply—growing her own food—but wasn’t as familiar with the farmer’s hardship as her partner. "It's frustrating how challenging something so simple is," Kami reflects after over a decade in the lifestyle. She married young and transitioned from rock climbing instructor to water buffalo farmer: "I wanted to find my limits and José was great for that. He's comfortable in a cardboard box."

They made cheese every day and lived in the tropical flatlands of Central Venezuela. Kami learned to cook piranha and crocodile and, when one was hit by the tractor, she was presented with a full-grown Boa constrictor to turn into dinner. She learned that every plant had a purpose. "Within a few months I knew it was going to be OK, it was where I wanted to be," she stated with an air of lust from her kitchen counter back in Colorado.

Isolation meant learning to do everything themselves and building a home took two years. José worked worked with groups of four or five men, toting chainsaws through the forest. Fence posts were based on, “the right tree, the right time, the right moon” mentality, he says. They were artists.

Their hard-earned paradise shadowed as 2002 brought the oil lockout. José and Kami were a seven-hour drive from Caracas. They couldn’t find food or medicine and were expecting their first born. Neighbors brought oil by the liter on the backs of pack donkeys. Kami was nearly full term and couldn’t track down her midwife. "I had watched animals do it plenty of times," she says, recalling how she and her husband trained their foreman to deliver their son if need be. The birth itself was the least of her worries; it was the uncertainty of corruption that infiltrated her dreams and blocked her from sleep. José had grown up here, he knew how things worked under the thumb of an authoritarian. She had no idea how bad things could get.

In the span of two months, Hugo Chávez had fired anyone of stature (doctors, teachers, etc.) and replaced them with confidants who would follow blindly. As a foreigner, Kami relied on José to judge when—if—to pull the plug. At the end of her final trimester, José woke her in the middle of the night after catching his cue to exit on the news. "OK, it's time," he said.

It took exactly one tank of gas to reach Caracas. They barely made it, military check points were common and one could never guess when a delay would pop up. Kami secured a record saying she was six months pregnant so she could fly. The expecting couple flew to Miami without a plan, drove to Dallas, and then to Eagle, CO where Kami’s brother lived. They found a midwife, met her, and the next day welcomed a healthy baby boy into their crumbling world.

Things in Venezuela were still bad, but it was home. They had assets so they went back, resurfacing in the U.S. a year later. They made another life for themselves on a ranch in Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley as their family grew. The same midwife who had delivered their first welcomed José and Kami’s second child, a daughter, into the world. She had become an important part of their stateside family when she was killed in a car accident the day after the delivery. Pummeled by another source of sadness, the family dusted themselves off and kept going, unsure as always to where they were, exactly, that was.

José started learning about renewable energy from his peers at a stint at Solar Energy International and eventually broke off to start a business of his own. Grounded Renewable Energy grew into a huge company they didn't really know what to do with. They had two kids and their very own slice of the American Dream. Listening to their story, I held my breath at this point, wanting to freeze them in this moment when things seemed perspectively easy, knowing the bottom fell out of this life, too.

Eventually, the company was sold to a bigger corporation that fired José and his business partner. José got the call while on vacation with his family. Contracts were fuzzy and in the end, his partner took everything. The family sold their house in Colorado and once more moved back to Venezuela’s high central plains.

They were welcomed by a gut-souring discovery. José’s father had sold the family ranch. The paradise they had expected to come back to had vanished. Calloused by their previous misfortune, the couple founded a new ranch in 2012, in a German-settled town near the coast. It was the planned site of an eco-village with several rustic homes, education opportunities that made up what the government’s rural education system lacked, and the financial promise of the backpacking circuit. "It was a fairyland," says Kami, "lightning bugs were everywhere."

They started producing meat and cheese again and just as quickly as their new-old life had started, cracks blemished its surface. The ranch was isolated, harboring loneliness and making education for their two sons a constant worry. Inflation was so high breaking the bank became routine. They would require a weekly raise of 100 Bolivares/week to keep up with inflation. Kami remembers not having enough money to buy a bag of rice. As José explains it, the only reason the country was not in a state of civil war was because the kidnapping of democracy happened too fast, too many people had left and not returned. Properties were pillaged like the Wild West. “They would kill you just to take your shoes,” recalls José, “you couldn’t escape it, even in the countryside.” Chavez broke up the largest ranchers, ate the cattle, burned fences. He gave small parcels of land to pseudo-farmers with no plan and no title. He sold land cheap to alliances and took big ranches from anyone else. Small farmers soon lost the motivation to defend their land and most fled the country.

When five men tied José, beat a farmhand and robbed the family of every morsel, it was once again time to call it. Kami and the boys fled north once again while José stayed behind to cut ties before abandoning the land: the mature fruit trees, herd of buffalo and cherried coffee plants. With inflation, it wasn't worth selling. They returned to Tybar once again, a place José had worked before working in solar energy. "I am where I was 10 years ago, just with two kids. Same thing, no money," he told me with a furrowed brow.

With no kin interested in taking it over, Tybar Ranch is for sale. José and Kami have plans but lack investors. “Chavez took advantage of much the same thing. The people who wanted to work the land didn’t own it,” says José. “You don't do anything handing someone land if there isn't a plan and a force behind it," he adds—and he's right. José and Kami have spent years learning how to build, manage and rebuild ranches. They have the grit it takes and then some, something new farmers must not only note, but fully realize before forming dreams based in a agri-fantasy. I probe him about what he thinks about the future of farming in America.

"The desire is there," he replies, “but the way we work our land is a broken system based solely on economics.”

He advises new small farmers to look beyond salary to find some solace in their good work. "Housing is provided, you can own your own animal, be outside; it’s the things outside the paycheck that you need to take advantage of," he says. Kami works off-site as a massage therapist, the rancher’s income won't make ends meet on its own.

The couple maintains a firm grip on their dream, both strengthened by their past and grounded in a sense of reality. Tybar has the potential to provide the skeleton for the eco-village crushed by Venezuelan politics, but comes with its own custom set of obstacles attached to U.S. land laws. Largely due to immense debt acquired by land leases in the U.S., over half of new farmers fold in the first three years. I asked José if he and Kami had plans to return to Venezuela, to try to fit the pieces back together and make it work again.

"Venezuela today is not the Venezuela I grew up in.” It was not so much void of emotion as a sure conclusion he had drawn from approaching the possibility from every last angle. Kami's sentiments about the plains are equally complex and simply stated: "The flatlands were great when we were young, but not now, not with kids."

Both José and Kami are the personification of ranching: the strength to enjoy the small things when the chips are perpetually stacked against you; the realization that what once was a good fit changes as a family swells and the world grows mad, and that loss is an important fact of life. As Kami puts it, "We do crisis well, it's the day-to-day of a stable life that's a challenge."